Ear defenders – also known as earmuffs or hearing protectors – are crucial safety devices designed to shield our ears from harmful noise. Whether on a noisy construction site or at a firing range, these devices can mean the difference between preserving your hearing and suffering irreversible damage. In this deep dive, we’ll explore how ear defenders work, the principles behind their noise reduction, the materials and design features that make them effective, and how they compare to earplugs. Along the way, we’ll cover the basics of sound and hearing to understand why protecting our ears is so important

Understanding Sound, Noise, and Hearing

Sound is a form of energy transmitted as waves through air (or other media). When something makes a noise – a loud machine, a musical instrument, a gunshot – it creates vibrations in the air. These pressure waves enter our ear and vibrate the eardrum, which in turn sends signals through tiny bones in the middle ear to the inner ear. In the inner ear, the cochlea (a fluid-filled, snail-shaped organ) houses thousands of microscopic hair cells that move with the vibrations and convert them into electrical nerve impulses. Our brain interprets these impulses as sound.

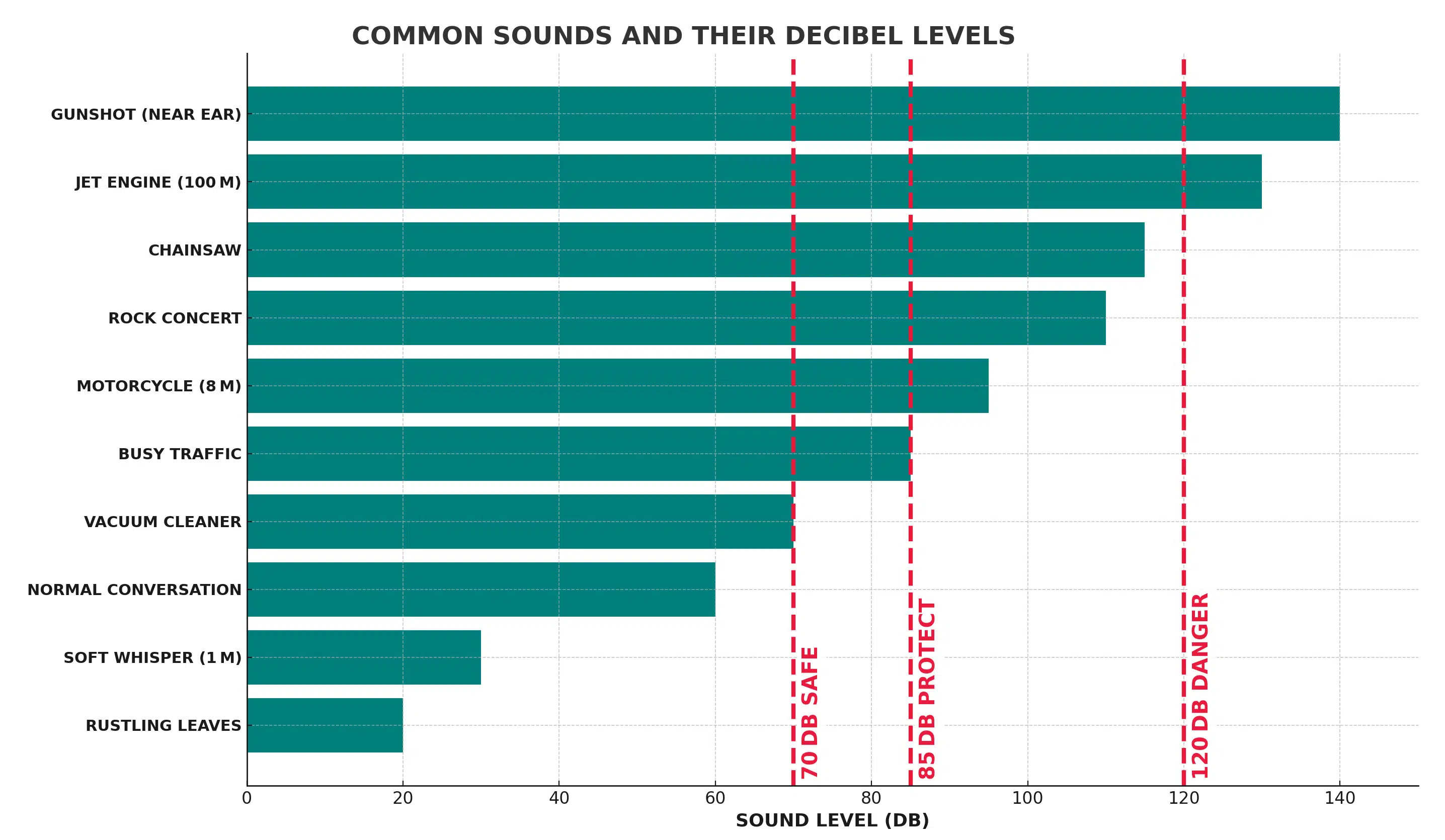

Decibels (dB) are the units we use to measure sound intensity. The decibel scale is logarithmic, meaning that a small increase in dB represents a big increase in sound energy. For example, an increase of 10 dB actually means the sound intensity is 10 times higher, and an increase of 20 dB means 100 times higher. A normal conversation might be around 60 dB, while a motorcycle or power drill can be 90 dB or more. Importantly, every 3 dB increase roughly doubles the sound intensity. This is why a noise that’s “only” 85 dB can be dangerous over time – it’s much more intense than it may seem.

Our ears can handle only so much noise. Exposure to loud sounds can damage those delicate hair cells in the cochlea. Once damaged, the hair cells do not regenerate – the hearing loss is permanent. The term noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is used for this kind of damage. NIHL often starts with losing the ability to hear high-pitched sounds and can be accompanied by tinnitus (ringing or buzzing in the ears). At first, you might notice temporary muffled hearing or ringing after a loud concert or a day of noisy work. This is a warning sign: you’ve experienced a temporary threshold shift. Repeated or intense exposures can lead to permanent threshold shifts – in other words, permanent hearing loss.

How loud is too loud? Audiologists and health authorities have set guidelines for safe noise exposure. Sound levels at or below about 70 dB(A) (A-weighted decibels, adjusted for human ear sensitivity) are generally considered safe indefinitely. Once levels reach 85 dB(A) and above, they become hazardous over long durations. At 85 dB, it is typically recommended to limit exposure to 8 hours (about a full workday) without protection For every 3 dB increase in noise above that, the safe exposure time halves. For instance, 88 dB might be safe for only 4 hours, 91 dB for 2 hours, and so on. A sudden impulse noise or blast at around 120 dB or more (for example, a firecracker or gunshot close by) can cause immediate damage to hearing in a single event.

To put these numbers in perspective, here is a chart of common sounds and their approximate levels:

We have a Noise Exposure & Hearing Protection Calculator you can use to find out what SNR you should be looking for when shopping for ear defenders.

Because harmful noise is so common – the U.S. CDC estimates tens of millions of workers are exposed to hazardous noise each year – hearing protection is essential in many situations. Regulatory bodies have set rules to help: for example, OSHA (the Occupational Safety & Health Administration in the U.S.) requires employers to implement hearing conservation measures if workers are exposed to an average of 85 dB or more over 8 hours. In the EU, regulations mandate that employers provide hearing protectors at exposures of 85 dB(A) and above, with an absolute exposure limit (with protection in place) of 87 dB. These regulations exist because prolonged noise exposure can sneak up on you – you might not notice the gradual hearing loss until it’s too late. By the time you’re shouting to communicate or your ears are ringing after work, the damage may already be happening.

Ear defenders come into play as an effective solution to prevent noise-induced hearing damage. They are part of a broader category of hearing protection devices (HPDs) that also includes earplugs and specialized noise helmets. The primary goal of any hearing protector is simple: reduce the intensity of sound reaching the eardrum to a safer level. However, as we’ll see, the way ear defenders achieve this (and how well they do it) involves some interesting science and engineering.

How Ear Defenders Block Noise

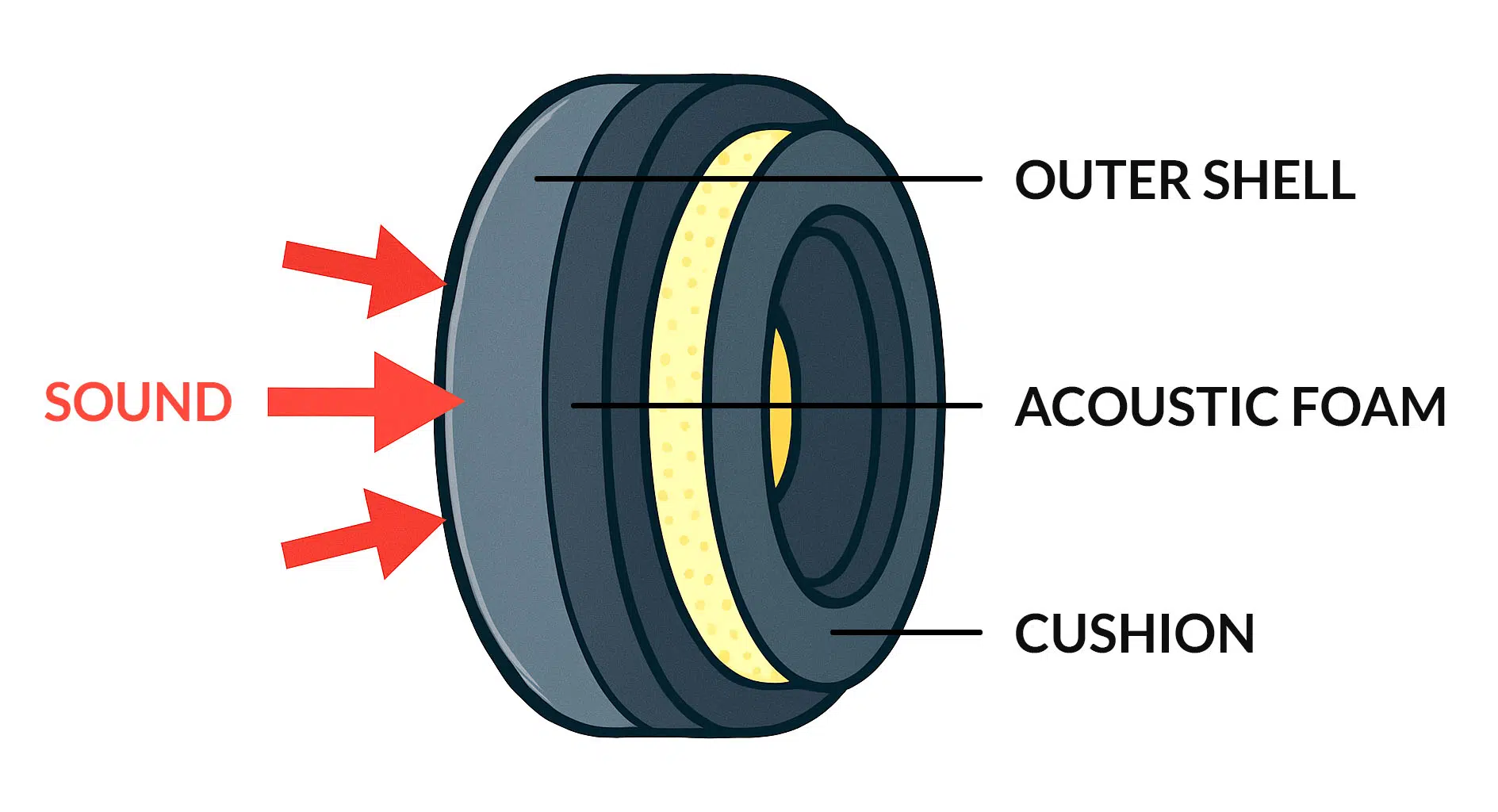

Ear defenders (acoustic earmuffs) are essentially barriers that block and absorb sound before it can reach your ears. They cover the entire outer ear, forming a seal against the head. Inside the muff, layers of sound-absorbing material dissipate the energy of the sound waves. Let’s break down how they work and the two main types available:

Passive Ear Defenders (Acoustic Earmuffs)

Passive ear defenders are the classic, non-electronic earmuff-style hearing protectors. If you’ve seen construction workers with big earmuffs or shooters at a gun range wearing headphone-like protectors, those are passive ear defenders. Their operation is entirely based on physical sound-blocking principles:

-

Sound isolation by coverage: The ear cups completely cover your outer ears (pinnae) and fit snugly against your head. By encompassing the ear, they create a closed space around the ear canal. This immediately reduces sound simply by blocking the direct air path for sound waves. It’s similar to how closing a door reduces noise from outside.

-

Acoustic foam absorption: The inside of each cup is lined with acoustic foam or fiber. This foam is a soft, porous material that absorbs sound waves by increasing air resistance, which in turn reduces the amplitude of the waves. As sound waves penetrate into the earmuff, the foam’s cells and channels make the air vibrate in tight, complex paths. The sound energy is essentially converted into tiny amounts of heat within the foam. By the time the waves pass through the foam, much of their energy is gone, and thus the sound that reaches the ear is greatly diminished.

-

Mass and barrier effect: The outer shell of a defender is usually a hard thermoplastic or metal layer. This hard wall reflects some sound waves, and by virtue of its mass, it resists vibrating in response to sound (especially important for blocking lower-frequency vibrations). The heavier and more rigid the cup, generally the better it can impede lower-frequency noise. This is because low-frequency sound has longer wavelengths and more energy, which is harder to stop; a massive barrier helps.

-

Seal and cushion: A critical component is the ear cushion that sits between the hard cup and your head. Typically made of soft foam or gel with a vinyl covering, this ring presses gently around your ear. It serves two purposes: comfort and sealing. A good seal means there are no gaps for sound to leak through. Even a small gap can let in a lot of sound (especially higher frequencies). Proper fit is everything – if hair, jewelry, or the temples of your eyeglasses break the seal even slightly, the protection drops. In fact, studies have found that safety glasses or other equipment that lift the cushion can reduce earmuff attenuation by 3 to 7 dB in certain frequency bands. That might not sound like much, but a 7 dB reduction could roughly double the sound energy getting through. This is why many earmuffs have soft, conformable cushions (sometimes even gel-filled) to mold around eyeglass arms and hair. It’s also why users are advised to remove thick earrings or ensure hair is pulled back where the cushions sit.

All these elements together allow passive earmuffs to typically reduce noise levels by a significant amount – often in the range of about 20 to 30 dB of attenuation for well-designed models. For example, a loud 100 dB noise outside the muff might be reduced to ~70–80 dB by the time it reaches the ear, which is a much safer level. The exact reduction varies with frequency: earmuffs usually attenuate mid and high frequencies (treble) more effectively than very low bass frequencies. Low-frequency sounds (like a deep rumble) are harder to block because they can vibrate the earmuff materials or even travel through the bones of the skull. In fact, ear defenders generally provide less attenuation below about 500 Hz. That’s one reason you might still sense a deep rumble from heavy machinery or engines even with earmuffs on – you’ll hear it less, but you might feel some of it. Earplugs, which seal the ear canal itself, can sometimes outperform earmuffs at those very low frequencies, but for most common noise frequencies, a good earmuff does an excellent job.

It’s important to use ear defenders correctly to get the full benefit. Placement and fit make a huge difference. The headband should press the cups firmly (but comfortably) against the head. Many earmuffs are adjustable – the cups slide on the headband to accommodate different head sizes. If the headband is worn behind the head or under the chin (some models allow this), ensure it’s still tight enough. If you ever feel that your earmuffs aren’t reducing noise as much as expected – for instance, if you can still clearly hear people talking at a normal volume – it could be that the seal is compromised or the earmuff isn’t fitted right. A quick test: with earmuffs on in a noisy area, press the cups tighter to your head with your hands; if the noise noticeably reduces when you do so, the earmuffs might not be tight enough or something is interfering with the seal (like glasses). In that case, adjust and try again.

Performance in practice: It’s worth noting that the labeled performance of ear defenders (more on ratings later) is often based on ideal conditions in a laboratory. In real-world use, factors like imperfect fit, movement, or degradation of the cushions can reduce the actual protection. However, one advantage earmuffs have over earplugs is consistency – it’s generally easier for an average person to achieve a decent fit with earmuffs, whereas earplugs can be inserted improperly. Research has shown that many users get only a fraction of the advertised attenuation from earplugs due to poor insertion, whereas earmuffs tend to perform closer to their ratings because they’re simpler to wear correctly. That said, even earmuffs can fall short if used incorrectly. Always make sure the cushions are soft and form a good seal and that the earmuff isn’t dislodged by bumps or other gear.

Limits of passive earmuffs: While passive ear defenders are very effective for a wide range of noise, they are not magic silence-makers. You will still hear some sounds – the goal is to reduce the noise to a safe level, not necessarily eliminate it. In extremely loud situations (for example, grinding metal in a confined space or standing next to a jet engine), even the best earmuffs might not attenuate enough on their own. In such cases, safety experts recommend double protection: wearing earplugs under earmuff ear defenders. Using dual protection can add an extra 5 to 10 dB of noise reduction beyond what either device provides alone. (You don’t just add the ratings together – the combined effect yields a smaller incremental benefit, often around +5 dB improvement over the higher-rated device). Dual protection is often used in ultra-high-noise jobs like airport ground crew work or military settings with explosives. If you go this route, remember that the earplug has to be inserted properly and the earmuff still needs a good seal over it.

Active (Electronic) Ear Defenders

While passive ear defenders rely purely on material science and physics, active ear defenders bring electronics into the mix to enhance protection and functionality. At first glance, active earmuffs look similar to passive ones – they have the same kind of ear cups and headband. The difference is that inside the cups, they contain microphones, speakers, and electronic circuitry. These components allow active earmuffs to do things passive ones cannot, essentially making them “smarter.” There are two main categories of active ear defender technology:

1. Level-Dependent Hearing Protectors (Sound Compression earmuffs): These are often just called “electronic earmuffs” or sometimes “amplification earmuffs.” They are popular with shooters, hunters, and certain industrial workers. The concept is clever: let safe sounds in, but keep harmful sounds out.

-

Each ear cup has a microphone on the outside that picks up ambient sounds. The sound is fed through an electronic amplifier circuit to speakers or drivers inside the ear cups that play the sound to your ears. In a quiet or moderately noisy environment, these earmuffs can actually act like hearing aids – amplifying faint sounds so you can hear better than you would with bare ears. For example, when hunting in the woods, electronic earmuffs might amplify the rustling of an animal in leaves or allow you to hear your friend talking in a normal voice.

-

The critical feature is that they have a built-in limiter or compressor. The electronics are calibrated so that if a sound exceeds a certain volume (usually around the safe limit of ~82–85 dB at the ear), the amplifier does not get louder. In fact, it will actively cap the output or even shut it off for that moment. So when a loud noise occurs – say a gunshot or a sudden bang – the system reacts almost instantly (within milliseconds). It either compresses the sound (reducing its volume to a safe level before sending it to the speaker) or clips it (momentarily turning off the speaker output to block the noise). The result: your ears are protected, as the sound you hear through the speakers never exceeds the safe threshold (often quoted around 82 dB for occupational safety).

-

From the user’s perspective, it’s almost magical. Imagine standing near someone using a hammer. With electronic earmuffs on, you can hear them speak and hear your surroundings clearly, but when they strike the hammer and that potentially 100+ dB noise occurs, you hear it only as a muted thump. The transition is typically fast enough that it feels seamless – you don’t hear a harsh cut-out; the loud sound is just reduced in volume. Some products refer to this as sound compression or level-dependent attenuation.

-

These earmuffs often include a volume control knob, allowing the wearer to adjust how much amplification they want. You might turn it up to hear tiny sounds when it’s quiet, or turn it down if you’re in a steady moderate noise. No matter the volume setting, the limiter will prevent it from ever passing the danger level. For instance, many models cap at 82 dB maximum output by design.

-

Use cases: Shooting sports are a prime example – on a shooting range you want to hear range commands, conversation, or the sound of an animal while hunting, but you need protection from gunshots. Electronic ear defenders excel here; they have become standard gear for many shooters. In construction or industrial settings, level-dependent muffs let workers hear machinery operating normally or hear warning shouts/alarms, but still guard them when a sudden loud event happens. Police and security officers might use them so they can remain situationally aware (hear footsteps, speech) yet be protected from explosions or firearm noise. Some advanced models even have stereo microphones (one on each side) to preserve directional hearing – this means you can tell where sound is coming from, which is important for situational awareness. With single-microphone designs (both sides feeding from one mic), it’s harder to locate sound directionally, so higher-end models often include one mic per ear cup.

-

Modern electronic earmuffs often add other convenient tech too: for example, an audio input jack or Bluetooth connectivity so you can listen to radio communications or music. Others integrate two-way radio systems for team communication (common in tactical and military headsets). These features make the earmuff a multi-purpose device: hearing protector, situational awareness aid, and communication headset all in one.

2. Active Noise Cancellation (ANC) Ear Defenders: Often labeled as ANR (Active Noise Reduction) in the context of hearing protection, this technology is akin to the noise-canceling headphones many people use for travel or office work, but ruggedized for high-noise environments. The principle is based on wave physics: if you can generate a sound wave that is the exact mirror opposite (inverse phase) of the incoming noise, the two waves will cancel each other out. Active noise-cancelling ear defenders use this to attack especially the low-frequency noise that passive methods struggle with.

-

These earmuffs have microphones inside or outside (or both) that sample the ambient noise. A built-in processor analyzes the sound and immediately generates an “anti-noise” – a sound wave equal in amplitude but inverted in phase (180° out of phase) to the noise. This anti-noise is fed through speakers inside the ear cups. When done correctly, the anti-noise wave meets the incoming noise wave and they interfere destructively, effectively flattening each other.

-

Active cancellation works best on continuous, predictable noise, especially in the low-frequency range. Examples include the droning of airplane engines, the rumble of heavy machinery or diesel generators, or the roar inside a tank or armored vehicle. These noises have fairly consistent wave patterns that the electronics can track and cancel. The effect is dramatic for the wearer – that deep rumble or hum significantly diminishes, creating a quieter background. Higher-frequency or sudden sounds are not canceled as effectively by ANC because they’re harder to predict and invert in real-time; however, those are usually already well-handled by the passive foam and seal of the earmuff.

-

Use cases: One of the most famous uses is in aviation headsets for pilots. In small aircraft or helicopters, engine and propeller noise can be intense, causing fatigue and potential hearing loss. Pilots use ANR headsets that cancel out the low-frequency engine drone, allowing them to hear radio communications and cockpit alerts more clearly (and protecting their hearing over long hours of flying). Another use is by heavy machine operators – for instance, a bulldozer or tractor operator might use ANR earmuffs to reduce the machine’s engine and exhaust noise. Military helicopter crews and tank crews also benefit greatly from ANR headsets, which help them communicate despite the surrounding noise.

-

Active noise cancelation is usually combined with the level-dependent features described above, and always built on top of a passive earmuff base. So an ANR headset typically also has the pass-through microphones for voices and limits loud sounds, etc. These tend to be the high-end hearing protectors, often with higher price tags, so they are used when maximum noise reduction is needed or for specialized professional applications.

One thing to note: active electronic ear defenders require power, typically batteries (some are rechargeable). If the batteries die, you lose the electronic functions (no amplification, no active cancelation), but you still have the passive protection of the muff itself. Most designs ensure that even “dead,” they function as ordinary earmuffs (though some ANC performance may rely on a good seal provided by active feedback – but generally you still get decent protection passively). It’s wise to keep fresh batteries on hand if you rely on the active features frequently.

In summary, active ear defenders enhance the basic protection of earmuffs with smart technology that adapts to the sound environment. They let the wearer communicate and stay aware of their surroundings, which can actually improve safety (you don’t have to lift your muff off to hear someone, which would expose you to a blast of noise). They also tackle the noises that are toughest to handle with passive materials alone. The end result is a safer and often more comfortable experience in extreme noise environments.

Design and Materials of Ear Defenders

Not all ear defenders are built the same – the materials and design details can greatly affect comfort, durability, and performance. Let’s look at what components make up a typical earmuff-style ear defender and the considerations that go into its design:

-

Headband: The headband is the part that goes over (or behind) your head and holds the two ear cups in place. Most headbands are made of metal (spring steel) or hard plastic. Steel headbands provide a consistent clamping force and are durable, while plastic headbands can be lighter and non-conductive (important for electrical work to avoid conducting electricity). Many headbands are adjustable – the cups can slide up and down to fit different head sizes and ear positions. The tension of the headband is carefully engineered: it must be tight enough to press the cups firmly for a good seal, but not so tight that it causes pain over long wear. Some headbands have a two-point suspension or a split band to distribute pressure evenly. Often the top of the band has a soft pad or is wide and curved to improve comfort on the skull, especially for heavy earmuffs.

-

Ear Cups (Shells): These are the hard outer part of the ear defender. As mentioned, they’re usually made from a tough thermoplastic like ABS. The shell’s job is to form a solid barrier and encase the insulation material. The shape is usually an oval cup that matches around the ear. Inside the cup, there’s often an open space (air cavity) in addition to the foam. The dimensions of this cavity and the shell thickness are tuned for acoustics – they can create resonant effects that help dampen sound at certain frequencies. High-end designs might use a double-walled shell or an internal damper to reduce resonance. Some ear cups include a small hole or vent with a tuned filter; this is done to improve low-frequency attenuation or to balance pressure, but it’s very carefully engineered so as not to leak too much sound. In specialized cases, manufacturers might incorporate heavy layers (like a thin sheet of lead or other metal) into the cup to block extremely high noise (weight and cost make this rare outside of special military or industrial headsets).

-

Acoustic Foam and Liner: Inside each ear cup is typically a foam liner. Often, there are two layers: a soft foam pad right behind the plastic shell, and a more open-cell foam that sits facing the ear (sometimes visible if you look inside an earmuff). The exact composition of these foams is proprietary to each manufacturer, but generally it’s a polyurethane foam formulated for sound absorption. The foam may be flat or sometimes egg-crate shaped. Its thickness and density affect what frequencies it absorbs best. Manufacturers design the foam setup to absorb a broad range of frequencies. Some earmuffs also include a thin film or membrane inside as a diaphragm to help tune the response (for example, to avoid over-attenuating certain speech frequencies so that warning shouts can still be a bit audible). All these pieces are part of the “secret sauce” that gives a particular model its noise reduction characteristics across frequencies.

-

Ear Cushions (Seals): The cushions are the rings that contact your head around your ears. They are usually made of a soft foam (often memory foam) encased in a flexible plastic or vinyl cover. Many modern earmuffs offer gel-filled cushions as an upgrade or option – these have a silicone gel that can be even more conforming and soft, which improves comfort and the quality of the seal (especially useful if you wear eyewear, as the gel can mold around glasses frames better). The cushion is perhaps the most critical comfort factor because this is what presses against your head for potentially hours. Good cushions minimize pressure points and spread the load evenly. Over time (or in cold weather), cheaper foam cushions can become stiff or crack, which both hurts comfort and reduces the acoustic seal. This is why it’s recommended to replace ear cushions periodically (many manufacturers suggest every 6 months to a year of regular use) to ensure the earmuff continues to work effectively. Some earmuffs come with hygiene kits – replacement cushions and foam liners – for this purpose. The cushions usually snap or stick onto the ear cups and can be removed for cleaning or replacement.

-

Adjustability and Attachment: Earmuffs can come in different mounting styles. The standard is the standalone headband as described. But there are also cap-mounted ear defenders that attach to hard hats or helmets via side slots – common in construction, forestry (like the orange hard hat with attached earmuffs and face shield in the image above), and other industries where head protection is also needed. These have specialized arms that clip into a hard hat and allow the earmuffs to swivel down over the ears or up out of the way when not needed. Another style is neckband earmuffs, where the band goes behind the neck or under the chin; these are often used when a hard hat or other headgear makes an over-head band impractical. The design of the attachment can affect how well the earmuff seals and how much pressure it applies, so each style is tested to meet the same standards.

-

Weight and Bulk: Generally, more material and heavier construction can mean better noise reduction (especially for low frequencies), but that also means a heavier device on the head. Manufacturers strive to keep ear defenders as light as possible without sacrificing performance. A typical high-attenuation earmuff might weigh anywhere from 200 to 400 grams. Newer materials and design optimizations have helped reduce weight. The physical size (cup size) also matters – larger cups can hold more foam and trap a bigger air volume (good for attenuation), but if they’re too large they may not fit well or could bump into other gear (like the stock of a rifle, or collar of a jacket). That’s why there are low-profile earmuffs designed for shooting, which trade a bit of attenuation for a slimmer cup that won’t get in the way when aiming.

-

Durability and Build: In industrial or military use, earmuffs must withstand rough treatment – being dropped, tossed in a toolbox, exposure to heat, cold, moisture, etc. The choice of materials (impact-resistant plastic, rust-proof metal) and features like hinges (for foldable models) are all about durability. Some defender models are foldable, collapsing into a compact form for storage; the hinge design needs to maintain clamping force over time. Others might have metal wire frames on the cups (especially cap-mounted types) that allow rotation and pivot – these need to be corrosion-resistant and strong. For use in electrical environments, dielectric earmuffs avoid any metal parts entirely, reducing the risk of electrical conduction or arcing (these are often all-plastic in construction but still meet the necessary strength).

-

Comfort features: Aside from soft cushions and padded headbands, some earmuffs include features like ventilated headbands (to reduce sweating on the top of the head) or even cooling gel inserts in the cushions to keep ears from getting too hot. While the primary job is protection, manufacturers know that if a device is uncomfortable, workers will be tempted not to wear it continuously – which defeats the purpose. So a lot of design effort goes into ergonomics: ensuring even pressure distribution, minimizing contact with sensitive parts of the ear, and making them as breathable as possible given they must seal air tightly.

In summary, the design of ear defenders is a balance between maximum noise reduction, comfort, and practicality. The best hearing protector is one that someone will wear properly for the full duration of the noise exposure. A super high-attenuation earmuff that’s painfully tight or hot will likely spend more time around the user’s neck than on their ears – and that’s a safety failure. Therefore, modern ear defenders aim to provide high levels of protection while remaining as comfortable as possible. When selecting a pair, you might notice specifications like the headband force or cushion material; these give clues to comfort. It’s also wise to consider the work environment – for example, in a hot factory, you might choose a model known for cooling or with moisture-wicking cushions.

Hearing Protection Ratings and Standards

When shopping for ear defenders or any hearing protection, you’ll encounter various ratings and standards on the packaging. These are meant to quantify how much noise reduction you can expect and to certify that the device meets certain safety requirements. Understanding these numbers helps ensure you choose the right protection for the noise level you’re facing.

Noise Reduction Rating (NRR): In the United States and some other countries, hearing protectors carry an NRR, a single-number rating measured in decibels. This number is determined in a laboratory test specified by standards (historically ANSI S3.19-1974 in the US, though newer methods exist). For example, you might see “NRR 29 dB” on a pair of earmuffs. In theory, this means if you wear the earmuffs correctly, you could expect the noise level at your ear to be reduced by 29 dB from the ambient level. If you were in a 100 dB environment, an NRR 29 protector might reduce the exposure to about 71 dB.

However, this simple subtraction is a bit optimistic for real-world use. The NRR is based on lab tests with ideal fitting by trained subjects, and it also includes some conservative adjustments. In practice, users often get less protection. In fact, OSHA and NIOSH (in the U.S.) have guidelines to derate the NRR for field use – a common rule of thumb is to subtract an additional safety factor (for example, OSHA sometimes suggests derating by 50% for earmuffs, and even more for earplugs). This is because of the differences between test conditions and real conditions (improper fit, movement, etc.). The positive side is that earmuffs tend to perform more consistently than plugs outside the lab, so you might get closer to the listed NRR in practice, but it’s rarely exact.

Single Number Rating (SNR): In Europe, products often use the SNR, which is conceptually similar to NRR. It’s part of the EN 352 standard series for hearing protectors. The SNR is also given in dB and is used to estimate how much the protector will reduce the noise. For example, an earmuff with SNR 25 dB, used in a workplace with 100 dB noise, would in theory reduce the level to about 75 dB at the ear. SNR testing is done per EN standards and might use slightly different methodologies, but to the user reading the box, SNR and NRR serve the same purpose: higher numbers mean more potential attenuation.

It’s important to note that these ratings are general indicators. The actual attenuation varies by frequency. That’s why standards also publish attenuation values across frequencies (like a table of how many dB the protector reduces at octave bands from 125 Hz up to 8000 Hz) and sometimes the H-M-L ratings (High, Medium, Low) which give a simplified idea of performance in high-, mid-, and low-frequency ranges. For instance, a protector might be rated H=33, M=29, L=20 dB, meaning it’s very good at blocking high-frequency noise (33 dB reduction), but less effective for low-frequency noise (20 dB reduction). Earmuffs generally show a drop-off in the L rating compared to earplugs, as mentioned before.

Standards and Certification: In order to be sold as hearing protection, ear defenders usually must comply with national or international standards. In the EU, EN 352 is the standard (with parts 1, 4, etc., covering earmuffs, electronic earmuffs, etc.). In the US, ANSI standards cover testing, and the EPA requires labeling of NRR on hearing protectors. Reputable products will have labels like “Tested to ANSI S12.6-2016” or “EN 352-1:2002 compliant,” which means they met the criteria in controlled tests.

For the end user, one practical aspect of standards is ensuring that hearing protectors are marked and labeled with their performance. So you’ll see the NRR or SNR on the product, sometimes along with a graph of attenuation by frequency. Additionally, industrial jobs often require hearing protectors to have certain certifications (like ANSI or CE marks) to be used as part of personal protective equipment (PPE) programs.

Using the ratings properly: The key is to choose a protector with an appropriate rating for your noise environment. You generally want to bring the noise at the ear down to below 85 dB. But more is not always better in an absolute sense; wearing an ultra-high attenuation muff in a moderate noise environment might isolate you too much (you can’t hear anything at all around you, which could be unsafe if you need to hear alarms or moving equipment). Also, extremely high attenuation protectors tend to be bulkier and potentially less comfortable. So for each job or situation, safety managers look at the noise levels and pick protectors with sufficient attenuation.

If noise levels are, say, 95 dB, a protector with 20 dB NRR should bring that to a safe 75 dB. If noise levels are 105 dB, you might aim for an earmuff with 30 dB NRR (which would theoretically bring it to 75 dB). If you only have something like 20 dB NRR in that 105 dB area, then double protection (earplug + earmuff) might be recommended. There is such a thing as over-protection: if you reduce sound too much, users may feel isolated or remove the protection to talk – a big no-no. The ideal is to attenuate just enough to be safe but still allow the person to function. This is why, for example, workers in 85-90 dB areas might use a lighter protector than workers in 110 dB areas.

Standards for special earmuffs: Active electronic earmuffs also have to meet standards. For instance, EN 352-4 covers level-dependent earmuffs, requiring that the shut-off or compression keeps sound under a certain level. This ensures that even with amplification, they won’t harm the user. Similarly, EN 352-6 covers earmuffs with communication capabilities, and EN 352-8 covers entertainment audio in earmuffs (like built-in radios or music players, making sure they don’t output dangerously high volume). All this is to say: when you see that a product meets these standards, you can trust that the fancy electronic features have been tested not to compromise the fundamental safety of the device.

Real-world vs lab performance: We touched on it, but to reiterate – the listed NRR/SNR is a laboratory number. In the field, an earmuff with NRR 30 might effectively give you 20–25 dB reduction if worn correctly, maybe less if worn poorly. The good news is that earmuffs are hard to “wear wrong” compared to plugs (which people often do not insert fully). One study cited by a hearing protection expert (Elliott Berger of 3M) pointed out that the actual attenuation achieved by typical users was often only 30%–70% of the labeled NRR for earmuffs (and even lower for earplugs). Earmuffs showed less variability and more reliability than plugs. So, while you should take the ratings as a guide, always err on the side of caution. If in doubt, go for a higher rating or use double protection in extreme noise.

Finally, keep your ear defenders in good shape to maintain their performance. Over time, check the cushions for cracks or loss of elasticity, and replace them if needed. Keep the foam inside dry (if they get soaked with sweat, let them dry out). Many ear defenders are dielectric (non-metallic), but if yours have metal parts, ensure they’re not bent or rusted. Store them in a way that the cushions don’t get permanently deformed (many foldable earmuffs come with a case or you can hang them on a hook). Following the manufacturer’s care instructions will ensure the device continues to meet the standards and performance it had when new.

Ear Defenders vs. Earplugs: A Comparison

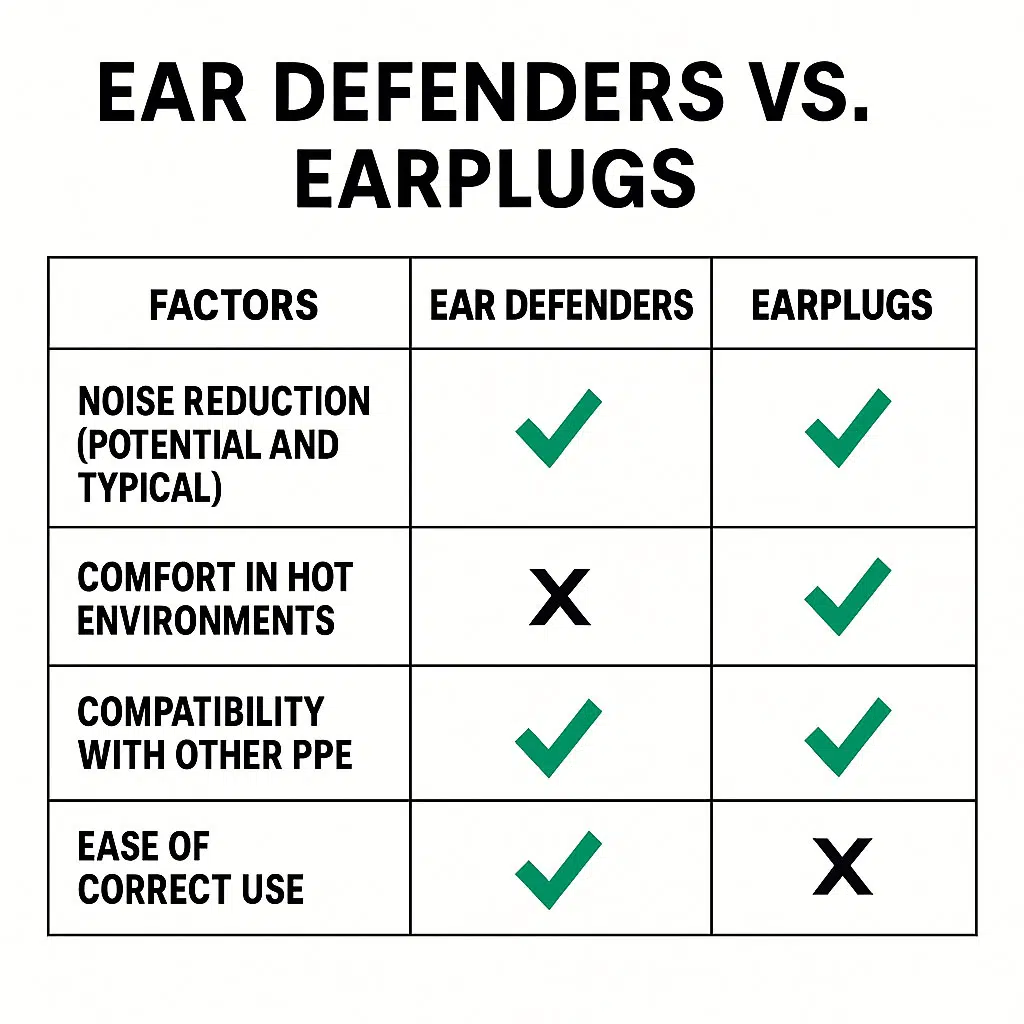

Ear defenders (earmuffs) are just one approach to hearing protection. Earplugs – the inserts that go into the ear canal – are the other common solution. Each type has its own advantages and disadvantages, and choosing between them (or deciding to use both) depends on the situation and personal preference. In this section, we’ll compare ear defenders and earplugs in terms of performance, comfort, and use cases.

Both ear defenders and earplugs, when used correctly, can provide significant noise reduction. In fact, earplugs often have a higher potential attenuation (especially for very low-frequency noise) because they block the ear canal directly. Foam earplugs can have an NRR in the high 20s or low 30s (dB), comparable to top-tier earmuffs. However, in practice, achieving that performance with earplugs can be tricky due to fit. Let’s break down the pros and cons:

Advantages of Ear Defenders (Earmuffs)

-

Easy to fit correctly: Ear muffs are essentially one-size-fits-all and don’t require special techniques to wear. You simply place them over your ears and adjust the headband. Most quality earmuffs are designed to accommodate a wide range of head sizes without much fuss. This means consistent protection – there’s a high likelihood you’ll get close to the advertised attenuation if you wear them as instructed. There’s no deep insertion or variability in ear canal shape to worry about, unlike earplugs.

-

Quick to put on and remove: If you’re in and out of noisy areas or need to talk frequently, earmuffs shine. You can lift them off your ears or around your neck in a second and put them back on just as fast. This makes them ideal for intermittent noise exposure – e.g., a technician who needs to enter a loud machine room occasionally can easily don and doff earmuffs. They also tend to be harder to misplace (you might hang them on a hook or around your neck when not in use).

-

One size fits most: Because they don’t go into the ear canal, there’s no issue of finding the right plug size or getting custom molds. A standard earmuff fits almost anyone (though for very small or very large heads, adjustable models cover that range). This is great in workplaces – you can issue the same model to everyone and not worry about sizing. It’s also handy for visitors or anyone who might share the equipment.

-

Visible compliance: It’s easy to see when someone is wearing earmuffs – they’re big and cover the ears. This is a practical advantage in workplaces; supervisors can quickly check that workers have their hearing protection on. With earplugs, from a distance it’s not obvious if someone has them inserted. The visibility of earmuffs can promote a culture of safety (and there’s less temptation to “cheat” because it’d be noticeable).

-

Additional features and warmth: As discussed, earmuffs can integrate electronics (amplification, radios, etc.) to enhance functionality. Earplugs generally cannot offer those features (with some high-tech military exceptions). Also, earmuffs keep your ears warm in cold weather as a bonus – a trait appreciated by outdoor workers in winter or by people using them in cold environments. They serve a dual purpose of hearing protection and earmwarmer. (There are even products marketed with high-visibility colors or reflecting stickers, adding to their utility on construction sites where being seen is important.)

-

Work with minor ear health issues: If someone has an ear infection, irritation, or cannot insert an earplug for some reason (ear surgery, etc.), earmuffs are a good alternative since they don’t physically go into the ear canal. You can also wear earmuffs over hearing aids (for those who have hearing loss and still need protection in noise) – whereas an earplug would block a hearing aid or require removing it.

Disadvantages of Ear Defenders

-

Bulky and heavy: Earmuffs are definitely bulkier than plugs. In hot or physically active environments, they can be perceived as cumbersome or hot to wear. They trap heat around the ears and can cause sweating in high temperatures or humid conditions. Some workers find them uncomfortable in these situations, describing them as making the sides of the head sweaty or pressing uncomfortably when worn for long durations (especially if also wearing tight helmet straps or eyewear).

-

Interference with other gear: If you need to wear a hard hat, safety glasses, a welding mask, respiratory mask, or even a thick winter hat, earmuffs might conflict. For example, standard over-headband earmuffs can’t be worn with many hard hats (hence the need for cap-mounted versions). Safety glasses, as mentioned, can break the seal if their frames are thick, reducing effectiveness. Earmuffs also might not fit well if you have a lot of hair (a big hairstyle or a thick beard that touches the cushion area can leak sound). Earplugs generally have none of these problems since they’re inside the ear canal.

-

Pressure and comfort for long wear: The clamping force can cause discomfort or even pain if too high. Some people are sensitive to having their ears compressed for hours. It can lead to headaches for certain individuals. While designs try to minimize this, wearing a heavy pair of muffs for an 8-12 hour shift can still be tiresome. Lighter models reduce this issue but might offer less noise reduction.

-

Less portable and more fragile: Earmuffs don’t fit in your pocket like earplugs do. If you’re traveling or moving between sites, carrying bulky earmuffs is an extra thing to manage. They can also break if squashed or dropped from a height – the plastic headbands can crack (especially in very cold weather if flexed) or the cushions can tear. Earplugs, especially disposable foam ones, are virtually indestructible in transport and you can carry spares easily.

-

Higher cost and maintenance: A good quality earmuff typically costs more upfront than a pack of earplugs (though they are reusable, so over time they may not be more expensive). They also require some minimal maintenance – wiping the cushions clean, replacing cushions every so often, and storing them properly. Earplugs, particularly disposables, are low-maintenance (use and toss). If earmuffs get dirty (grease, dust), you have to take care to clean them for hygiene – which in some workplaces is a consideration.

-

Limited use in tight spaces: In very confined areas or if you have to lie down with your head sideways, earmuffs can get in the way because of their bulk. An electrician squeezing into a crawlspace or a mechanic under a car might find them snagging or preventing their head from fitting in a tight spot. Low-profile earmuffs attempt to solve this but earplugs inherently don’t have that issue at all.

Advantages of Earplugs

-

High potential protection: Because earplugs seal the ear canal, they can block sound very effectively, especially high-frequency noise. A deeply inserted foam earplug can offer extremely high attenuation (lab NRRs of 30-33 dB for some foam plugs). In very loud environments (airports, foundries, gun ranges), well-fitted earplugs often outperform earmuffs for total reduction, particularly for low-frequency noise where the plug reduces the sound that would otherwise transmit through the ear canal and bone. In fact, for some extremely loud situations, double protection is used with the earplug taking a primary role and the earmuff adding extra on top.

-

Comfort in hot environments: Earplugs are lightweight and unobtrusive. In hot or physically demanding work, earplugs won’t make you feel hot; they don’t cover your ears so they allow natural heat dissipation. Many people find a soft foam or silicone plug, once properly inserted, basically unnoticeable after a few minutes. There’s no external pressure on your head. For long shifts in hot factories or outdoor summer construction, earplugs can be much more comfortable than earmuffs which trap heat.

-

No interference with other equipment: You can wear earplugs with any other personal protective equipment. Hard hat, goggles, face shield, respirator mask – no problem. There’s nothing external to get in the way. This makes earplugs very versatile for combining with other safety gear. For example, someone doing abrasive blasting might have a full face respirator and a hood; earmuffs might not fit under that, but earplugs will. Plugs also work under motorcycle or aviation helmets where earmuffs could never fit (motorcyclists often use earplugs under their helmet to reduce wind noise).

-

Portable and convenient: Earplugs, especially disposables, can be carried in a pocket or small case. You can always have a pair on hand. They’re also low-profile – you can wear them without it being very obvious (for instance, if you’re at a loud concert and don’t want big earmuffs, small plugs are discreet). Because they are cheap, you can stash multiple pairs in different places (your car, your toolbox, etc.) so you’re never caught without protection.

-

Hygiene and single-use options: Disposable earplugs are meant to be single-use, which can be a pro in dirty environments – you use them once and throw away, avoiding the need to clean them. There are also reusable plugs that can be washed. Earmuffs on the other hand can get dirty and you have to keep using the same pair unless you swap out cushions. In situations where sanitation is critical (like food manufacturing or cleanrooms), often they prefer earplugs (and sometimes even metal-detectable plugs so if they fall out they can be found in product, which is a specialized use).

-

Specialized earplugs (custom and high-fidelity): For certain groups like musicians, there are custom-molded earplugs or high-fidelity plugs that reduce volume evenly across frequencies (so music still sounds good, just quieter). Ear defenders generally don’t provide that kind of frequency-balanced attenuation (they tend to cut more highs). So earplugs can be tailored for scenarios where sound quality matters (concerts, orchestras, etc.) – a big reason many performing artists use plugs over muffs.

Disadvantages of Earplugs

-

Fit variability and user error: The biggest downside is that earplugs must be inserted correctly to work well, and many people do it wrong. Foam earplugs, for example, need to be rolled tightly, inserted deep into the canal, and held in place while they expand. If you just stick it at the opening of the ear, it might only give a fraction of the protection. Improperly fitted earplugs can reduce the expected protection by 50% or more. It often requires training and practice to insert plugs properly (in workplace hearing conservation programs, fit testing is becoming common – where they measure how well the plug works in your ear to teach proper insertion). Additionally, every person’s ear canal size and shape is different. A plug that seals one person’s ear may not seal another’s. Some people need different sizes or types of plugs (small ear canals, for instance, may require smaller foam plugs or flanged plugs). Custom-molded plugs solve this but are more expensive.

-

Can be uncomfortable in the ear: Some people find the feeling of earplugs intrusive or irritating, especially if worn for long periods. They can cause pressure in the ear canal, or in some cases, lead to ear canal abrasions if not smooth. If your ears are sensitive or you’re prone to ear infections, plugs might aggravate that. There’s also a slight risk of pushing a plug too deep or not being able to get it out easily (especially with DIY foam bits – one reason to always use proper earplugs with some kind of handle or string if you worry about that).

-

Hygiene and dirt: In dirty or dusty environments, you have to be careful with earplugs. Since you’re putting them into your ear, your fingers ideally should be clean to avoid pushing dirt or bacteria inside. Foam plugs tend to collect dirt and earwax and are not really cleanable (hence disposable). Reusable plugs must be cleaned periodically or they can grow bacteria. On the flip side, earmuffs just wipe clean and you’re not touching your inner ear to put them on. So for quick intermittent use by many different people, earmuffs are more hygienic (plugs should not be shared unless they’re disposables and thrown after use). If one is working with very dirty hands, taking an earplug in and out could introduce grime into the ear.

-

May fall out or lose seal during activity: If an earplug is not well seated or if you’re talking/moving your jaw a lot (which can slightly shift your ear canal shape), plugs can work their way loose. Once a plug backs out even a little, the protection drops markedly. People with chewing gum or talking jobs sometimes find they have to reseat their earplugs occasionally. And unlike earmuffs, you might not notice immediately that a plug has loosened until you suddenly hear the noise get louder. Also, their small size makes them easy to lose if they fall out. Earmuffs basically hang around your neck when not on, but an earplug could drop to the floor unnoticed.

-

Limited communication ability: Regular earplugs will block all sound (including speech) to a similar degree, making it hard to hear others or equipment sounds. While earmuffs also muffle sound, you can lift them up for a moment to talk (or use electronic ones to hear speech). With earplugs, people often end up partially removing one to hear someone talking, which is a risky habit. There are level-dependent earplugs on the market (with acoustic filters that let soft sounds in and block loud sounds), and even electronic earplugs, but these are more specialized. In general, communication is trickier with plugs unless you pair them with other systems (like radio headsets worn over plugs, which the military sometimes does).

In summary, ear defenders vs earplugs is not a one-size-fits-all choice. Each has strengths that lend themselves to certain scenarios. Many workplaces actually provide both and let workers choose, or even encourage double protection in extreme noise.

Here’s a quick comparison to sum it up:

-

Ear Defenders (Earmuffs): Easiest to use correctly, bulkier to wear, great for intermittent use and when you need to quickly remove/replace, can include electronics for hearing ambient sounds or communication, uncomfortable in heat, can conflict with other gear, higher upfront cost but reusable.

-

Earplugs: Highly portable and low-profile, better for continuous wear in hot or confined environments, no external bulk, cheap (especially disposables), but highly dependent on proper insertion, harder to monitor usage (can’t tell if someone’s wearing them), and require clean handling.

Which should you choose? It often comes down to the situation:

-

If you need maximum protection (e.g., jackhammering in a tight space) or you’re wearing other headgear, earplugs might be the better choice.

-

If you need to take hearing protection on and off, or you want the added features and easier compliance, ear defenders might be ideal.

-

In some cases, using both together is the best solution for extreme noise (remember to account for the fact that protection is not simply additive – you get diminishing returns by doubling up, but it does help).

It’s also a matter of personal comfort. Some people simply prefer one over the other. What’s crucial is that some form of effective hearing protection is used consistently whenever noise levels are hazardous. The greatest attenuation in the world means nothing if the device sits on the bench instead of on your ear or in your ear.

Types of Ear Defenders and Their Applications

Ear defenders come in various models tailored to different environments and purposes. While the core mechanism (blocking noise) is the same, features can vary to suit industrial worksites versus shooting ranges versus airports. Here we’ll explore a few common categories of ear defenders by application:

Industrial and Workplace Ear Defenders

In industrial settings such as construction sites, factories, mines, or any work environment with loud machinery, hearing protection is often mandatory. Ear defenders for these uses prioritize high noise reduction, durability, and compatibility with other safety gear.

-

High Attenuation for Loud Machinery: Industrial noise can include a mix of continuous noise (engines, motors, generators) and impact noise (hammering, stamping machines). Ear defenders for these jobs typically have a high NRR/SNR to bring down noise levels well into the safe zone. For example, a construction worker operating a loud concrete saw (which might be ~100 dB) will use earmuffs that offer around 25-30 dB of attenuation, aiming to reduce that exposure to the 70-75 dB range.

-

Hard Hat Mounted Designs: Many construction and mining workers wear hard hats, so ear defender manufacturers offer cap-mounted earmuffs that attach directly to the helmet. The image above of the orange hard hat with orange earmuffs is a classic example used in forestry: loggers often wear a hard hat with integrated ear defenders and a face visor. These earmuffs swivel outward when not in use and snap over the ears when needed. They are tested to ensure the helmet seal and earmuff seal don’t interfere with each other. This setup is convenient and ensures that whenever the hard hat is worn (required in many sites), hearing protection is readily available as part of the ensemble.

-

Durability and Washability: Workplace earmuffs are built tough. They may have metal reinforcement in headbands, and the plastics used are often resistant to oils, solvents, and UV light (for outdoor use). Cushions on industrial models are usually easy to clean or replace, since they might get dirty with sweat or grime. Bright colors (neon yellow, orange, red) are popular for industrial earmuffs so they’re visible (this helps with compliance monitoring and also finding them if misplaced on a site).

-

Communication and Situational Awareness: In certain industries, workers need to hear important sounds like warning alarms, backup beepers on trucks, or colleagues shouting instructions. As a result, level-dependent (electronic) ear defenders are increasingly used in workplaces too. For instance, a groundskeeper using noisy lawn equipment might wear electronic earmuffs that allow them to hear a coworker yelling their name but still protect them from the lawnmower’s roar. Similarly, some factory workers use electronic earmuffs tuned to amplify speech frequencies so they can converse (at safe volumes) while still wearing protection. Another aspect is integrated communication systems: for teams like crane operators, airlines ground crew, or firefighters, there are earmuff headsets with built-in two-way radios. A good example is airport ground staff who guide planes – they wear heavy-duty earmuffs with an attached microphone, so they can talk to the cockpit and each other despite standing next to screaming jet engines.

-

Specialty Features: Industrial models may have features like dielectrically safe construction (for electricians, with no exposed metal), or high-visibility reflectors for night work. Some are “smart” – connecting to phones or radios via Bluetooth for communication or even monitoring noise exposure and reporting data. These advanced earmuffs are part of the trend of “smart PPE” that not only protect but also provide information.

In an industrial context, hearing protectors are often standardized: a company might issue the same earmuff model to all workers in a certain noise class. Training is provided so everyone knows how to wear and care for them. It’s also common that such workplaces enforce Hearing Protection Zones – areas where you must have ear protection on, typically indicated by signs (e.g., “Hearing Protection Required Beyond This Point”). Ear defenders suitable for industrial use will have the necessary certification to meet occupational safety regulations, and they might also be tested for other factors like flammability (for use in hot work areas like welding or cutting, where sparks might land on them, they shouldn’t easily catch fire or melt onto skin

Shooting Sports and Firearms Use

Perhaps one of the most recognized uses of ear defenders is in shooting sports, hunting, and military firearms training. The sound of gunfire is extremely loud – a typical pistol or rifle gunshot ranges from 140 to 170 dB at the shooter’s ear. These impulsive noises can cause immediate hearing damage if unprotected. Thus, ear protection is absolutely essential whenever firearms are used, even for a single shot.

For shooters, ear defenders have some special considerations:

-

Instantaneous Protection: Gunshots create a very fast, sharp noise. Electronic active earmuffs are particularly valued here because they react immediately. They allow the shooter to hear surrounding sounds (crucial for hunting to hear game, or on a range to hear range officer commands), but will instantly clamp down when the firearm is discharged. Typically, shooting earmuffs will shut off amplification above ~82 dB, so the gunshot’s report is reduced to a safe level. This happens so fast (often in microseconds) that the shooter might only hear a subdued pop. After the shot, the earmuff returns to the ambient listening mode.

-

Stereo Sound and Direction: In shooting and hunting, situational awareness can be a matter of safety and success (knowing where others are, or where an animal is moving). Therefore, stereo electronic earmuffs (with two microphones, one on each cup) are common. They preserve directional hearing – you can tell if a twig snapped to your left or right, which is important in hunting, and you can identify where a range command came from, etc. Some advanced shooting earmuffs even have 360° situational awareness features or multiple microphones to better pick up sound from all around.

-

Low Profile Design: Many shooters prefer earmuffs that are slimmer in profile, especially on the lower part of the cup, so that the muff doesn’t bump the rifle or shotgun stock. A bulky earmuff can interfere with getting a proper cheek weld on the stock or could get nudged by the firearm, breaking the seal momentarily. Thus, manufacturers make “cut-away” or low-profile earmuffs for shooting, which have a tapered bottom edge. These might have slightly less passive attenuation because there’s less volume and material, but they strike a balance between protection and ergonomics for shooting posture.

-

Comfort for long sessions: Shooting sessions or a day at the range can mean hours of wearing hearing protection. Earmuffs used here tend to emphasize comfort – thick soft cushions (often replaceable), and lightweight builds. Also, many shooting ear defenders are foldable for easy storage in a range bag.

-

Hunting considerations: When hunting, one might opt for earplugs or electronic in-ear protectors instead, because earmuffs can sometimes be awkward (especially rifle hunting) and can amplify noises like wind. However, there are hunters who use earmuff-style electronic protectors, especially in situations like duck hunting (where you might be wearing a hat and not moving through brush a lot) or target shooting in the field. The earmuffs have the advantage of not needing to be inserted, which is good when you might want to quickly take them on/off to listen carefully to the environment. Electronic muffs can even amplify distant animal sounds beyond normal hearing levels (some have gain that makes you feel you have “super hearing” until the gunshot comes and it suppresses it).

-

Double protection for indoor ranges: Indoor shooting ranges are notoriously loud environments, as the sound reverberates in the enclosed space. It’s common for shooters and range officers in indoor ranges to double up (earplugs + earmuffs) due to the intense and frequent gunshots. Over-ear defenders will reduce the sound significantly, and adding plugs can further cut the peak noise of gunshots which can have very high pressure levels. The combination is highly effective and recommended for magnum or high-caliber firearms indoors. In such cases, one might use a lighter earmuff (for comfort) on top of plugs because the plugs are doing a lot of the heavy lifting for attenuation, and the earmuff provides additional reduction plus acts as a backup if you need to momentarily remove one (say to talk – though ideally one shouldn’t remove either in active fire situations).

-

Military and tactical use: Soldiers and law enforcement have some of the most advanced hearing protection systems, often termed Tactical Communication and Protective Systems (TCAPS). These are essentially fancy electronic ear defenders that integrate with helmets and radios. They perform the same function – protect from gunshots and explosions while allowing ambient sound – but are built into the troops’ communication network (so everyone can hear radio comms in their headset). They also are ruggedized and sometimes waterproof. An example is active noise-reducing headsets worn by artillery crews or special forces; they can hear each other on intercom and still not be deafened by gunfire or even mild blast waves. While beyond the consumer market, it’s interesting that the technology in your shooting earmuffs at the range is akin to what’s used in these tactical units – just scaled up in complexity and cost.

Electronic ear defenders are popular in shooting sports. They allow shooters to hear range commands and ambient sounds but instantly protect the ears from the deafening noise of gunfire.

In summary, for shooting and firearms, ear defenders provide indispensable, instantaneous hearing protection. Whether one chooses earmuffs or plugs (or both), the key is ensuring ample protection because the noise levels are among the highest humans encounter. Many lifelong shooters without proper protection suffer severe hearing loss and tinnitus – hence the strong emphasis in modern times on always wearing hearing protection when firing guns. Ear defenders designed for shooting make it as convenient as possible to do so, without impeding the activity.

Aviation and Heavy Equipment

The aviation field is another domain where ear defenders are critical. Think of airport ground crew working near jet engines, or pilots sitting in a small propeller plane’s cockpit for hours. The noise can be intense and continuous. Similarly, operators of heavy equipment (bulldozers, excavators, tanks, ships) face loud engine and mechanical noise for prolonged periods.

-

Airport Ground Crew: These workers direct aircraft on the ground, load baggage, service the planes, etc. A running jet engine at close range can easily exceed 130 dB. Ramp crews commonly wear high-attenuation earmuffs, often in combination with earplugs (double protection) because of the extreme noise. Their ear defenders also frequently include communication systems – for example, a ramp marshaller guiding a plane might have a headset that connects to the pilot or the control tower so they can coordinate. These headsets are usually over-the-ear defenders with a built-in microphone (boom mic) and sometimes ANR technology to cancel the engine drone so the speech communication is clear. They are built tough to withstand outdoor weather and jet blast (wind). You’ll notice they often have bright colors and reflective tape too, for visibility on the tarmac.

-

Pilots (and Passengers in small aircraft): Inside an aircraft, hearing protection is also needed, albeit the approach is slightly different. In commercial airliners, passengers may use simple earplugs or nothing (the cabins are somewhat insulated, though still loud enough that many people use earplugs or noise-cancelling headphones to be comfortable). But for pilots of small planes or helicopters, ANR headsets are the gold standard. These look like earmuffs with a headband and microphone, very much like ear defenders because they are – they include thick ear cups for passive noise reduction and active noise cancellation to tackle the low-frequency engine and propeller noise. Pilots need to hear radio communications and audible alarms, so these headsets don’t fully block all sound; they reduce the roar to a background murmur while letting voice frequencies through clearly (often via the intercom system). They also often allow pilots to play music or hear phone calls (via Bluetooth) during long flights, but with volume limiting for safety. One famous example is the Bose aviation headsets which are ANR and prized for their comfort and noise reduction – many pilots invest in these to reduce fatigue and protect their hearing over a career.

-

Helicopter crews: Helicopters have a unique high-pitch rotor noise and engine whine. Helicopter headsets are similar to fixed-wing pilot headsets, usually with ANR as well to handle the strong low-frequency blade “wop wop” and high-frequency turbine sound. Military helicopter crews (like Blackhawk or Chinook crews) often wear integrated helmets with hearing protection built in, combining both earcup attenuation and sometimes additional earplugs. The idea is to protect them during continuous operation and also in case of sudden loud events (like gunfire or explosions nearby).

-

Heavy Machinery Operators: People who operate things like bulldozers, excavators, dump trucks, cranes, generators, etc., usually are exposed to loud engine noise and sometimes hydraulic noise all day. Many of these vehicles are open-cab or only lightly insulated. Over time, that noise can cause hearing loss. Operators often choose earmuff-style protectors for ease – for example, a crane operator might wear electronic earmuffs so they can hear a colleague on the ground via radio, while drowning out the engine and mechanical sounds. Some construction equipment cabs now have built-in noise reduction and sound systems for communication, but personal hearing protection is still a must in most cases.

-

Communications: A big theme in aviation and heavy equipment is communication. Unlike a factory floor where maybe people can see each other, a pilot or a vehicle operator needs a comm system. Ear defenders in these fields almost always have a comm component: either the ear defender is part of a comm headset or it’s used in combination with separate comm gear (some operators wear slim earplugs and then put a communications headset that doesn’t fully cover the ear because the plug is handling the protection). However, the integrated approach (like a Peltor aviation headset or David Clark headset – common brands in aviation) is convenient and effective.

-

Active Noise Cancellation in these settings: We mentioned ANR for pilots. Similarly, some high-end industrial earmuffs include ANR specifically for things like long-haul truckers or miners in very loud machines. The ANR can reduce the rumble and help the user not feel as “drained” by the end of the day. That being said, ANR in industrial use isn’t as widespread due to cost and the need for power, but it’s found in niche applications (and likely to grow as tech costs come down).

It’s noteworthy that in these professional settings, hearing protectors are as much a productivity and comfort tool as they are safety equipment. A pilot who isn’t exhausted by noise will be more alert. A driver of a huge dump truck who can still hear the two-way radio clearly will be safer. So the ear defender designs here really focus on integrating hearing protection seamlessly with the work’s communication demands.

Entertainment and Concerts

Concerts, live events, and other entertainment venues present a dilemma: you’re there to hear sound – music or cheers – yet that very sound can be harmful in high doses. Sound levels at concerts or clubs often reach 100 dB or above, which can cause hearing damage with prolonged exposure. While earplugs are more commonly associated with concert-goers and musicians (especially high-fidelity musician’s earplugs), ear defenders also have a place in certain entertainment settings.

-

Concert and Festival Staff: People working sound engineering, stage crew, or security at concerts might opt for earmuffs for convenience. For instance, a stage crew member might wear a communication headset (which doubles as hearing protection) so they can get cues via radio while still being protected from the loud music or pyrotechnics booms. Security personnel at a concert might wear earmuffs if they need to be able to take them on and off quickly to talk to attendees (though many use plugs). One advantage of earmuffs in a concert setting for staff is visibility – it signals to others that “I have hearing protection on” and maybe why you might not hear someone unless they tap you. Also, branded or color-coded earmuffs can identify staff easily in a crowd.

-

Attendees and Spectators: It’s becoming more common (and socially accepted) for people in the audience to use hearing protection. While most use earplugs (small foam or musician’s plugs), some people do use ear defenders, especially at outdoor festivals or extremely loud events. For example, at motor races, monster truck rallies, or airshows (which we can include in entertainment), you will see lots of fans young and old wearing big ear defenders. The benefit is they are easy to put on kids and adults alike, and they often have enough attenuation to handle the sudden roars and bangs. At a rock concert, wearing big earmuffs might feel a bit cumbersome in a packed crowd, but it’s not unheard of – particularly for people who are very cautious about their hearing or perhaps those who didn’t get a chance to buy earplugs and pick up a pair of earmuffs from a vendor.

-

Musicians and Performers: Most musicians use specially filtered earplugs or in-ear monitors rather than earmuffs, because earmuffs make it hard to perform (imagine trying to play violin or sing with big shells over your ears – you can’t hear the nuance or your own voice correctly). However, there are cases: drummers in studio or practice settings sometimes wear isolation headphones (which are essentially ear defenders with audio feed) to protect their ears from the drum kit while listening to a metronome or music track. Some sound techs might wear earmuffs when checking loud equipment or during sound check when there are bursts of very loud noise (like feedback) possible.

-

Cinemas and Theaters: Modern movie theaters can hit peak sound levels that are quite loud (action scenes can reach 90-100 dB). Usually it’s not enough to require hearing protection for the 2-3 hour duration, but individuals sensitive to loud sounds might choose to wear earmuffs or plugs. Also, employees running certain special effects or working near speaker stacks in theme parks might use ear defenders for protection.

-

Clubs and DJs: In nightclub environments, usually people prefer smaller earplugs to maintain the scene’s aesthetics and ease of movement. Earmuffs are rare on the dance floor. However, some DJs or bouncers might use them in extreme cases. DJs often use one earcup of headphones to monitor music – those DJ headphones are not really hearing protectors (they might even add to volume). It’s worth noting an interesting crossover: some companies make high-fidelity earmuffs or hearing protector headphones that include audio drivers, aiming to function as both hearing protection and high-quality headphones for listening to music at safe levels. These could be used by sound mixers or concert staff to hear a feed while blocking the external din.

-

Spectator Sports (Motorsports especially): While not “music,” events like drag racing, NASCAR, Formula 1, or even demolition derbies are entertainment and are extremely loud. Many spectators wear ear defenders – often you’ll see families with children all wearing earmuffs at these events (since children’s ears are particularly sensitive and you want to protect them). Organizers sometimes even hand out or sell earmuffs at these venues branded with the event logo. The reason earmuffs are favored here is ease of use (you can take them off between races if you want to talk, etc.) and better attenuation of the very loud, often low-frequency-heavy noise (like the rumble of a dragster engine). Also, you can wear earmuffs over a baseball cap or sunhat, which is common at outdoor tracks.

In entertainment contexts, a major goal of hearing protection is to reduce the sound to a safe level while preserving the quality of the experience as much as possible. Earmuffs tend to muffle and bass-boost the sound a bit (because they naturally cut more highs than lows), so music might sound different. High-fidelity earplugs are usually preferred by audiophiles for this reason – they have a flatter attenuation profile. But for casual protection and especially for extremely high volumes, earmuffs do a great job and are user-friendly.

As we’ve seen, ear defenders are versatile and come in many flavors – from the simple foam-lined cups for mowing your lawn, to the high-tech electronic headsets used by fighter pilots. No matter the scenario, the core principle remains: reducing harmful noise before it reaches your ears. The design tweaks and additional features simply tailor that core function to the needs of the moment, whether it’s communication, comfort, or convenience.

Conclusion

Our ability to hear the world around us is something many of us take for granted – until it’s diminished. Noise-induced hearing loss is permanent but completely preventable. Ear defenders, in their various forms, are among the most effective tools we have to guard against this invisible threat. By understanding how ear defenders work – from the physics of sound absorption in foam to the clever electronics that cancel noise – we can better appreciate why using them consistently is so important in noisy environments.

When used properly, hearing protectors can literally save your hearing for the rest of your life. The key takeaways from this deep dive:

-

Ear defenders (earmuffs) create a sealed barrier around the ears and use sound-absorbing materials to significantly reduce noise levels before they hit your eardrums.

-

They come in passive and active varieties, with active ear defenders offering smart features that allow you to hear what you need to (like voices or alarms) while still blocking dangerous noises.

-

The effectiveness of ear defenders depends on good design and proper fit – a well-made earmuff with a good seal can attenuate noise by 20-30 dB or more, making a hazardous noise level safer to endure.

-

In choosing hearing protection, consider the environment: ear defenders excel in many situations, while earplugs have their own advantages in others. Often the best solution is what you find most comfortable and will wear correctly every time.

-

There are specialized ear defender models for nearly every application, be it shooting, aviation, industrial work, or enjoying a rock concert. Whatever loud activity you plan to do, there’s likely a hearing protection solution tailored for it.

For those interested in using ear defenders, a few final practical tips: always follow the manufacturer’s instructions (especially for any electronic features), keep the cushions and bands in good condition, and store them in a clean, dry place. If you ever feel your ear defenders are not performing as well (you start noticing noise is louder than it used to be with them on), it might be time to replace the cushions or the unit. And remember, hearing protection only works when it’s on your ears before the noise starts – be proactive, not reactive, about wearing it.

In conclusion, ear defenders are a proven, effective means to safeguard one of our most vital senses. They embody a mix of straightforward physics and advanced technology, all geared toward one goal: keeping your hearing safe. In a world that is only getting noisier, understanding and utilizing hearing protection is more important than ever. So the next time you fire up a chainsaw, attend a Grand Prix, or head into the factory, you’ll know exactly how those earmuffs slung around your neck are going to protect you – and you can wear them with confidence, knowing the science is solidly on your side (or rather, on your ears).

Stay safe, and enjoy the sounds of life at safe volumes!